Vernacular Wax Cylinder Recordings at the UCSB Library

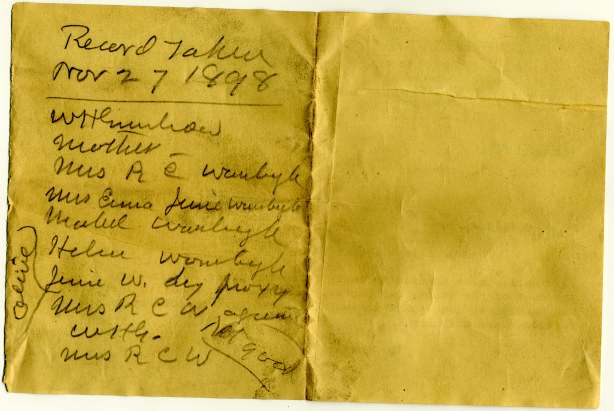

Slip accompanying recording of Rachel C. Wombough (1815-1903), the earliest-born American woman known to exist on record.

The UCSB Library’s Department of Special Collections houses more than 650 vernacular wax cylinder recordings, or home wax recordings, from the 1890s through the 1920s that capture the early spirit of the public’s interaction with recording technology. In March 2015 the collection was added to the 2014 National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress and may be the world’s largest and most diverse collection of early vernacular sound recordings.

The bulk of the collection is from the David Giovannoni Collection of Home Cylinder Recordings at the University of California Santa Barbara. It offers a unique opportunity to time-travel through sound—to eavesdrop on the private lives of our forebears. We hope that making the collection available online for all to hear will lead to a new appreciation and understanding of this rich but overlooked part of our heritage of historic recorded sound.

The home recordings found in this collection weren’t always literally made in people’s homes. Instead, they’re the audio equivalent of what Richard Chalfen calls the “home-mode of visual communication”1—which is to say, they involve the use of media for intimate, private, and personal purposes rather than public, impersonal ones. They can be distinguished both from commercial recordings made by the recording industry for popular exhibition and sale and from field recordings made by collectors for institutional preservation and academic study.

For many years, home recordings weren’t valued as highly as commercial or field recordings. Even today, some phonograph enthusiasts are all-too-ready to shave home-recorded cylinders from a century or more ago to reuse the blanks for making new recordings. To some extent, then, this represents a longterm, concerted rescue operation. Its nucleus was assembled in the 1970s and 1980s by Don Hill, one of the first people to recognize the value of home recordings as anthropological artifacts. David Giovannoni acquired Hill’s collection in the mid-1990s and added steadily to it up until the time of its acquisition by USCB in 2013.

Home, commercial, and field recordings can all feature vernacular performance traditions, oral histories, and the like, but commercial and field recordings have generally been initiated by outsiders for their own purposes and shaped with those purposes in mind. The recording industry has aimed to capture material that will sell, while fieldworkers have sought to document specific kinds of material that are of academic or artistic interest to them. By contrast, home recordings are made by and among groups of family and friends for their own use and enjoyment. The act of recording doesn’t intrude on the vernacular performance context as it does in the other cases, but instead heightens and extends it. We get to hear what ordinary people chose to record, and how they chose to adapt it to the medium, when they were in charge of the equipment and weren’t being told what to do by someone else.

And the results are often astounding. Together with hymns well-known and obscure, Stephen Foster songs, and umpteen rounds of “Marching Through Georgia,” the collection contains:

- The oldest known recordings of American vernacular fiddle music, including two announced as made in 1900 and 1905.

- Recordings of traditional songs, many of which would not be captured as audio by ethnographic fieldworkers until decades later. These are often heard here in versions that differ significantly from those documented elsewhere, as with “Boring For Oil,” “El Soldado Americano,” and “Mrs. McLaughlin’s Party.” Others combine traditional elements in unique ways or present songs that seem otherwise to have vanished without a trace, as with “Arkansas Pat” and one unidentified song about Irish emigration to America.

- An authentic record of the squealing of pigs and other barnyard sounds—one of the earliest surviving recordings of real animal noises as opposed to human imitations of them.

- A recording of British banjo virtuoso David Milner playing “at home.”

- A series of brief speeches commemorating January 1, 1900.

- Probably the earliest extant recordings of the songs “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and “Oh, My Darling Clementine,” although exact recording dates aren’t known.

- A phonographic sales pitch for the Vikings’ Remedy, a wholesome medicine that “cures when doctors fail,” but that is otherwise lost to history.

- At least three independent efforts by different people to call their dogs by phonograph in the spirit of “His Master’s Voice.” (Cylinders 13057, 13219, 13222, 13263)

- Singing by a Civil War veteran of the Second Maine Cavalry.

- Numerous amateur recitations, including Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and two dialect pieces authored by African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar: “In the Morning” and “Breaking the Charm.”

- Mendel Jonas—a Jewish clothier of Goshen, New York—listing in German the major events of his life during a gathering on his sixty-fourth birthday, noting among other things his birth in Deutsch Ostrowo (now Ostrów Wielkopolski) in 1842, his Prussian military service in 1864, and his emigration to America in 1866.

Three “channel rim” cylinders from the North American period contain the oldest dated recordings in the collection (1893, 1894, and 1895). There may be recordings as old or older but their dates are not stated in the recordings themselves.

The collection also contains larger groupings of cylinders created by the same people and discovered together years later, providing more in-depth coverage of the lives of some individual families and communities. Among these sets are:

- The William Henry Greenhow Collection (7 cylinders): William Henry Greenhow (1845-1918) was the publisher of the Hornell (New York) Evening Tribune, and the cylinders he recorded between 1898 and 1902 are notable partly for the sheer age of the people whose voices we hear on them. These include his mother, Mary Frodsham Greenhow (1823-1906), who sings some of his “childhood songs,” and his late sister’s mother-in-law, Rachel C. Wombough (1815-1903), who talks about her late husband coming to Addison County in 1804, and who is the earliest-born American woman whose voice is known to survive on record—P. T. Barnum, born in 1810, is the only American with an earlier birthdate whose recorded voice we can hear today. Another highlight of the set is a cylinder recorded on the fiftieth anniversary of the wedding of David and Olive Wellever, which had taken place in 1850; Olive’s sister Rebecca reminisces into the phonograph about “how the bride was dressed fifty years ago.”

- Rittersville Collection (21 cylinders): Featuring the Rittersville Choir and Sunday School, a brass band, and local performers on cornet, piano, and organ, this collection furnishes an impressive overview of the turn-of-the-century musical life of this Eastern Pennsylvania village, since annexed by Allentown, Pennsylvania.

- The F. E. Moses Collection (28 cylinders): This collection was created between 1908 and 1911 by the family of Franzi Enoch Moses (1857-1947), a stock farmer of Wayne County, Nebraska. Moses had been the first settler in what is now Brenna Precinct, which he had named in memory of his late sister Brenna—one of the cylinders is also announced as a “Brenna Record” made on “Brenna Ranch.” Three generations of the Moses family are represented here telling stories, performing music on flute or violin, or giving talks on subjects ranging from prehistoric man to the cultivation of alfalfa to the direct election of senators. We also hear a lively instrumental duet by the family’s Swedish immigrant neighbors, Olof and Christina Anderson, and a mock auction of the Moses farm by local farmer and real estate agent Clyde Oman.

- The Florian Fuchs Collection (33 cylinders): The son of a Lower Austrian butter-maker and innkeeper, Florian Fuchs (1870-1928) immigrated to the United States as a teenager in 1887 and settled in Pierce County, Nebraska, where he married, had ten children, and prospered as the proprietor of Valley View Stock Farm. In 1912, he took a trip back to his native country and visited the village of Ullrichs, where he had been born and raised. While he was there, his relatives and their friends recorded a wide assortment of cylinders for him, including spoken messages of goodwill, singing with zither accompaniment, a traditional Brautlied or bridal song, and even the tolling of the local church bell, giving him a unique audio self-portrait of his home community to take back with him to America.

- The Frank Lawrence Embree Collection (37 cylinders): Frank Lawrence Embree (b. 1863) pursued a varied career as a book and art dealer, publisher, agent for an antique furniture concern, composer, poet, and purveyor—through his Arabian Fruits Company—of a constipation remedy compounded of raisins, prunes, dates, and figs. He spent much of his working life in New York City, but he also maintained a summer residence called Duck-Puddle Farm near Bristol, Maine, and bred dogs in Charlestown, New Hampshire. To entertain himself and his family and friends while he was away from the metropolis in these places, he had a Columbia Graphophone together with a large assortment of commercially prerecorded cylinders. He also had a recorder, and while he made some straightforward home recordings with it, he also used it in some less typical ways. Whenever a guest came to call, Embree liked to take a commercially prerecorded cylinder and record a customized message to “Mister Graphophone” in the blank space left over at the end as a quick demonstration of how well the machine could reproduce his speech. At other times, he would instead drop his recorder into the middle of a commercial music cylinder and record himself singing or whistling along with the music, giving us some of the earliest known examples of sound-on-sound overdubbing. Embree let his talking machine languish for a while shortly after the turn of the century, but in 1915 he dusted it off for another chat with “Mister Graphophone,” reflecting on what a good friend it had been in years past. “All of these records will be very interesting in time to come,” he remarked, “when all these people have passed away.”

–Patrick Feaster, December 2013.

Click here to see a list of all the recordings that make up the David Giovannoni Collection of Home Cylinder Recordings. For a list of all of the home recordings in the library's collection, click here.

1. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/2602/BSS%2013%2019-25.pdf